Reasons to see poverty beyond monetary reductionism

Published:

Since the beginning of the national emergency due to the advance of Covid19, in Peru, as in other countries, it has been urgent to serve populations that, given their characteristics, are more vulnerable than others: the poor. Conventionally, one way to identify these people is through monetary measurements, which evaluate households through their spending: if given their income they cannot consume a minimum basket1, they are poor, otherwise they are not. Although this approach allows the construction of indicators that have a simple measurement and understanding, there are currently several studies that indicate that “purchasing behavior is only part of the defining characteristic of poverty”2. In this framework, I propose to offer some reasons to start measuring poverty from a multidimensional plane3.

Let us start by saying that today there is a global recognition of the importance of having a comprehensive measure of multidimensional poverty that captures multiple deprivations faced by the poor and that provides information on its intensity and composition. Here it should be clarified that multidimensional measures are not contrary to traditional monetary measurements, but rather seek to complement them by reflecting relevant aspects of poverty that can hardly be tracked using only one-dimensional variables such as consumption or income.

The first reason for having a multidimensional measure of poverty is empirical: monetary poverty is not a good proxy for the most important non-monetary deprivations. To illustrate this, let’s take the example that the PUCP Institute for Human Development in Latin America (IDHAL, Spanish acronym) made taking as reference a bulletin recently published by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), one of the main institutions focused on calculation of multidimensional poverty worldwide. The IDHAL has carried out some calculations to identify the Peruvian population that, based on certain deficiencies that they suffer in various dimensions of their well-being, could be at greater risk due to the advance of Covid19 and compared them with the figures of monetary poverty in the country to assess whether these measures are consistent.

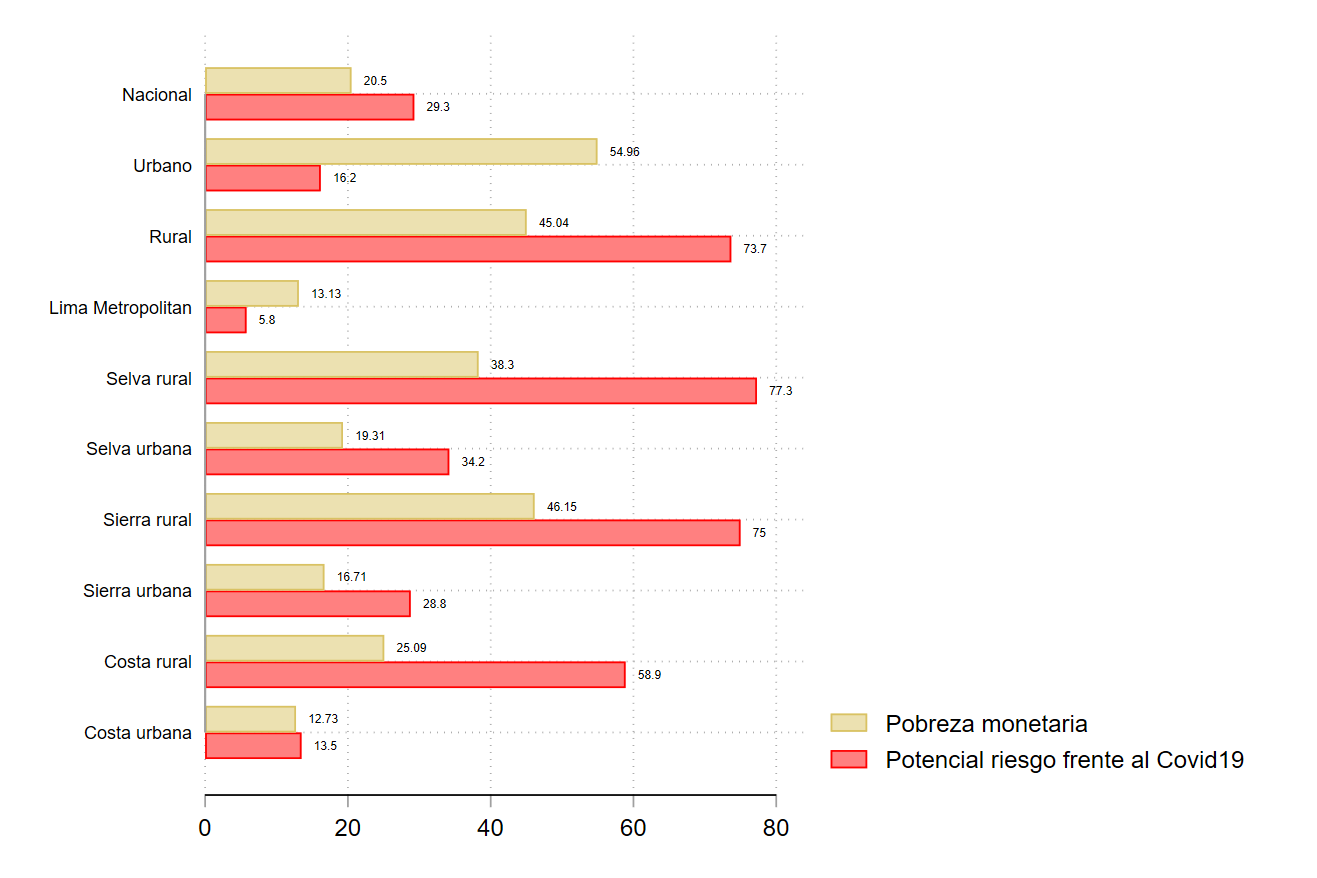

For its analysis, the IDHAL considered the following indicators to identify the population most at risk: lack of access to water, lack of access to sanitation, use of polluting fuels for cooking, overcrowding, lack of access to a refrigerator, and the presence of people with chronic diseases at home. A rather striking aspect was that, when comparing the incidence of people in situations of potential risk with the levels of monetary poverty, in most cases this measurement of poverty did not allow the existence of a set of key non-monetary deprivations to be identified. In the following graph I add to the IDHAL calculations, the monetary poverty values calculated with the 2018 National Household Survey (ENAHO, Spanish acronym) for a better understanding of this matter.

Figure 1. Peru: Monetary poverty and incidence of people in situations of potential risk against Covid19 (they suffer from deficiencies in 3 or more of the 6 deprivation indicators) by domain, 2018

Source: INEI - ENAHO 2018 and IDHAL (2020). Own elaboration based on the article Covid-19 and Multidimensional Poverty in Peru of the IDHAL-PUCP.

Likewise, the IDHAL identifies that the population that can be considered at risk against Covid19 and that is in rural areas is hardly mapped with the monetary poverty approach. The data indicates that, in the rural coast, mountains and jungle, the percentage of people who suffer from at least 3 of the 6 deprivations and who are not identified as monetary poor is, in all cases, greater than 37%. Thus, we have that monetary poverty measures are very useful, but they need to be complemented with multidimensional indicators to provide a more comprehensive view of poverty.

There is also a technical reason to begin to see poverty multidimensionally and this is the computational and methodological development that today allows processing and analyzing large amounts of information. Note that historically monetary poverty measures emerged in a context in which the various deprivations of the population could not be easily mapped, but it was more feasible to quantify income and consumption.

On this point, it seems important to me to highlight Carolina Trivelli’s opinion on the existence of various measures of poverty. According to her, the most relevant thing is not to have an exhaustive list of poverty measurements, but what is really important is to have useful measures to identify and monitor poverty and “how” it is reduced. Thus, to the extent that monetary poverty is not a good proxy for multidimensional poverty, it is not able to reliably predict changes in these deprivations over time. Showing what the poor are like and what deprivations they face, as well as tracking poverty over time are some of the purposes of multidimensional poverty measurements4.

There is also a political reason for betting on a multidimensional and official measurement of poverty, and that is that this approach encourages the coordinated actions of multiple sectors and ministries. Multidimensional poverty would not only complement monetary measures and inform about who and how the poor are, but also by providing information on the multiple deprivations they face, it would require joint strategies to reduce their incidence while guiding a better budget allocation. In this regard, Jhonatan Clausen of the IDHAL points out that the recent experience of the “Multisectoral Plan to Fight Anemia” can be a good example on this point.

Finally, beyond the empirical, technical and political reasons to measure poverty in a multidimensional way, there is a greater reason to begin to consider that poverty has multiple edges and that is an ethical reason. Seeing poverty only through monetary lenses confronts us with the risk of leaving millions of people behind who may experience underemployment, food insecurity, overcrowding, and many other deprivations that are not necessarily captured through income and consumption. Committing to the poor and their multiple needs also requires action to address these broader problems.

We have seen that there are sufficient reasons to begin to quantify poverty from a broader level. Although there will surely be those who consider that one more measure does not solve the problem of the poor and that we should rather focus on the fact that these people are no longer in this situation, it is clear that there will be no successful intervention to remove millions from vulnerability of people if we do not end up identifying them properly and recognizing that their deficiencies are particular and are subject to the different contexts to which they belong. It is in moments like the one we live in that unfortunately we begin to realize how necessary it is to start looking at the poor beyond monetary reductionism and in which we consider the need for an inspiring approach to public policies and social programs more comprehensive.

References

INEI. (2019). Perú: Evolución de los Indicadores de Empleo e Ingreso por Departamento, 2007-2018. Lima: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática.

According to INEI (2019), the monetary approach considers people in households whose per capita spending is insufficient to acquire a basic basket of food and non-food (housing, clothing, education, health, transportation, etc.) to be poor. Likewise, those from households whose per capita expenses are below even the cost of the basic food basket are extremely poor. ↩

See for example the paper by Caterina Ruggeri et al. (2003) “Does it matter that we do not agree on the definition of poverty? A comparison of four approaches” showing an example for Peru and India. ↩

These reasons are based on the first chapter of the book Multidimensional poverty measurement and analysis by Sabina Alkire et al. (2015). ↩

Keep in mind that Objective 1.2 of the Sustainable Development Goals that Peru has signed indicates that as a commitment that countries have signed is monitoring progress in reducing other “forms” of non-monetary poverty.. ↩