Some data on those most affected by COVID19 in Peru: The informal workers (Part II)

Published:

As discussed in the previous article, given the mandatory social immobility ordered by the Peruvian government to reduce the advance of COVID19, most of the economic activities have been interrupted, threatening the payment chain and maintaining the living conditions of the population. The government has put in place measures to support the most vulnerable populations through subsidies. At first, these measures were directed at the country’s poor. More recently, the creation of the Bono Independiente has been announced, an economic subsidy aimed at workers with incomes of less than 1,200 soles (353 USD) and who are not on the payroll of the public or private sector (780,000 vulnerable households)1. In other words, this new bonus will focus mainly on workers with informal jobs; And, for a better understanding of who they are and what their main characteristics are, the following lines come.

Economists have studied informality from different theoretical perspectives. On the one hand, most currents of economic thought study informality as a result of the economic choice of individuals who decide to operate outside the legal and regulatory frameworks that govern economic activity (Schneider & Enste, 2000). Thus, individuals take into account the costs of formality and decide to operate outside it. Another theoretical current points out that informal self-employment in Third World countries can be seen as excess supply in the labor market in a typically overcrowded society in which workers make a second-order choice (Figueroa, 2015). Thus, even if the costs of operating formally disappeared, there would continue to be a subsistence sector in which workers who cannot find wage employment seek self-employment in legal or illegal activities.

On the one hand, in the Peruvian case, the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (2018) defines informal jobs as those that do not have the benefits stipulated by the Law such as access to social security paid by the employer, paid vacations , sick leave, etc. Informal jobs are: i) employers and own account of the informal sector, ii) wage earners without social security (formal and informal), iii) unpaid family workers (formal and informal) and domestic workers without social benefits. On the other hand, some of the stylized facts that have attracted attention in Peru in this regard are that: i) despite sustained economic growth, informality persists and has not disappeared, taking new forms; ii) there is low mobility from informal employment to formal employment; iii) informal workers receive the least income: a formal worker earns almost twice as much as an informal worker; and, iv) high informality reduces productivity and exacerbates inequalities (CEPLAN, 2016).

According to the National Household Survey (ENAHO), for the year 2018, the employed population with informal employment in Peru was 12 million 152 thousand people, which would represent 72.4% of the total employed workforce. Likewise, 78.3% of said jobs would be within the informal sector and the remaining 21.7% outside the informal sector, since there are institutional sectors that by definition are “formal” but still informally employ the workforce.

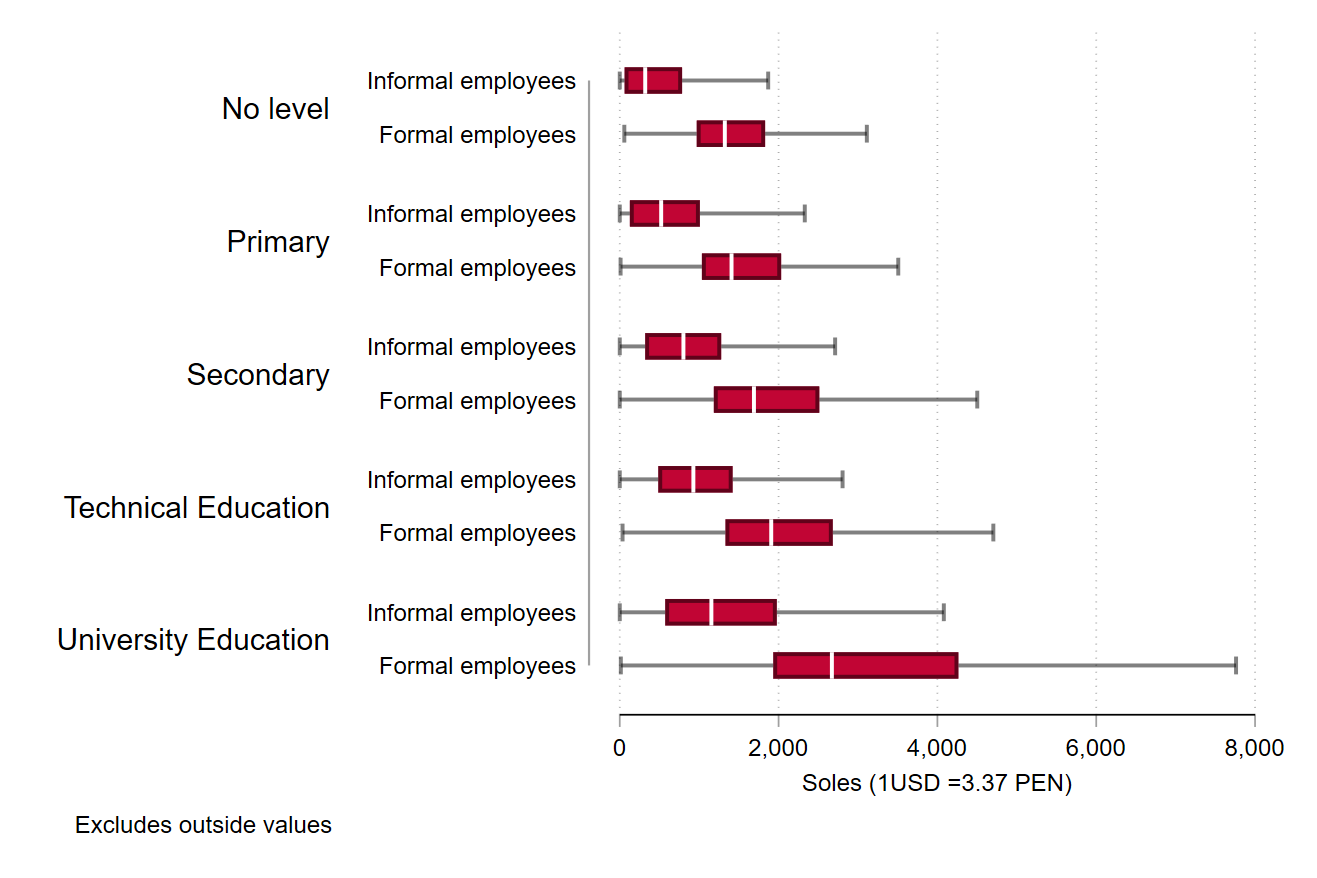

In Peru, informality of employment is higher in women (75.3%) in relation to men (70.2%). Likewise, this is a phenomenon that mainly affects young people aged 17 years and younger (99.6%) and adults aged 65 years and over (85.3%). According to educational level, the highest informality rates are found in people with lower educational levels: without level (95.7%), primary (90.7%) and secondary (72.4%). Furthermore, considering almost any educational level attained, the income of workers with formal jobs is almost double that of informal workers.

Figure 1. Peru: Average labor income of informal and informal workers by educational level, 2018 (percentages)

Source: ENAHO - INEI. Own elaboration.

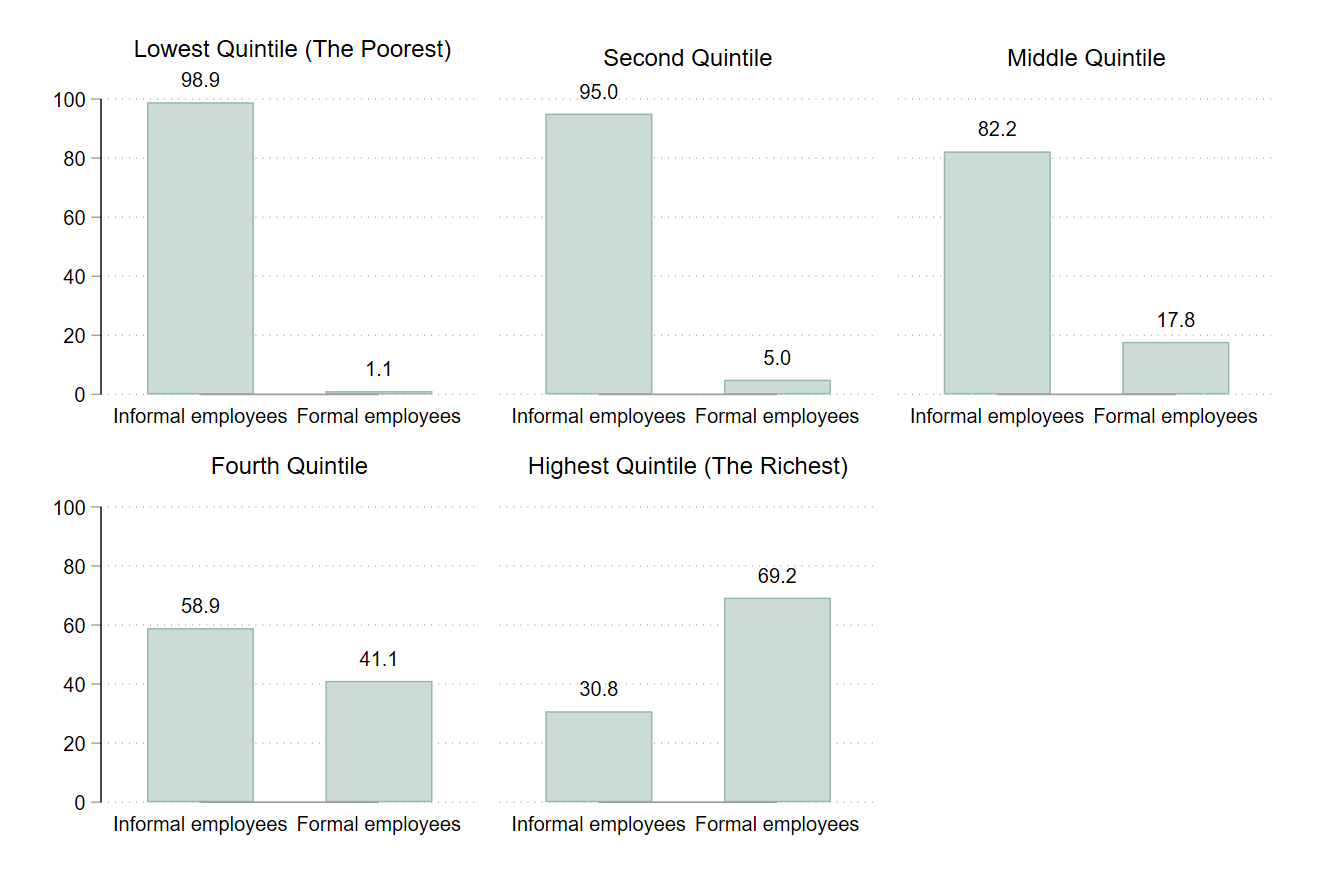

As stated in the previous article, a very important characteristic of the poor is the fact of having informal employment (93.1% of the working-age poor who are employed are informal). With a greater disaggregation, it is observed that informality is almost total in the quintiles with the lowest labor income (98.9% in the first quintile). However, it should be noted that even in the highest income quintiles there are informal jobs (30.8% in the fifth quintile).

Figure 2. Peru: Labor informality according to employment income quintiles, 2018 (percentages)

Source: ENAHO - INEI. Own elaboration.

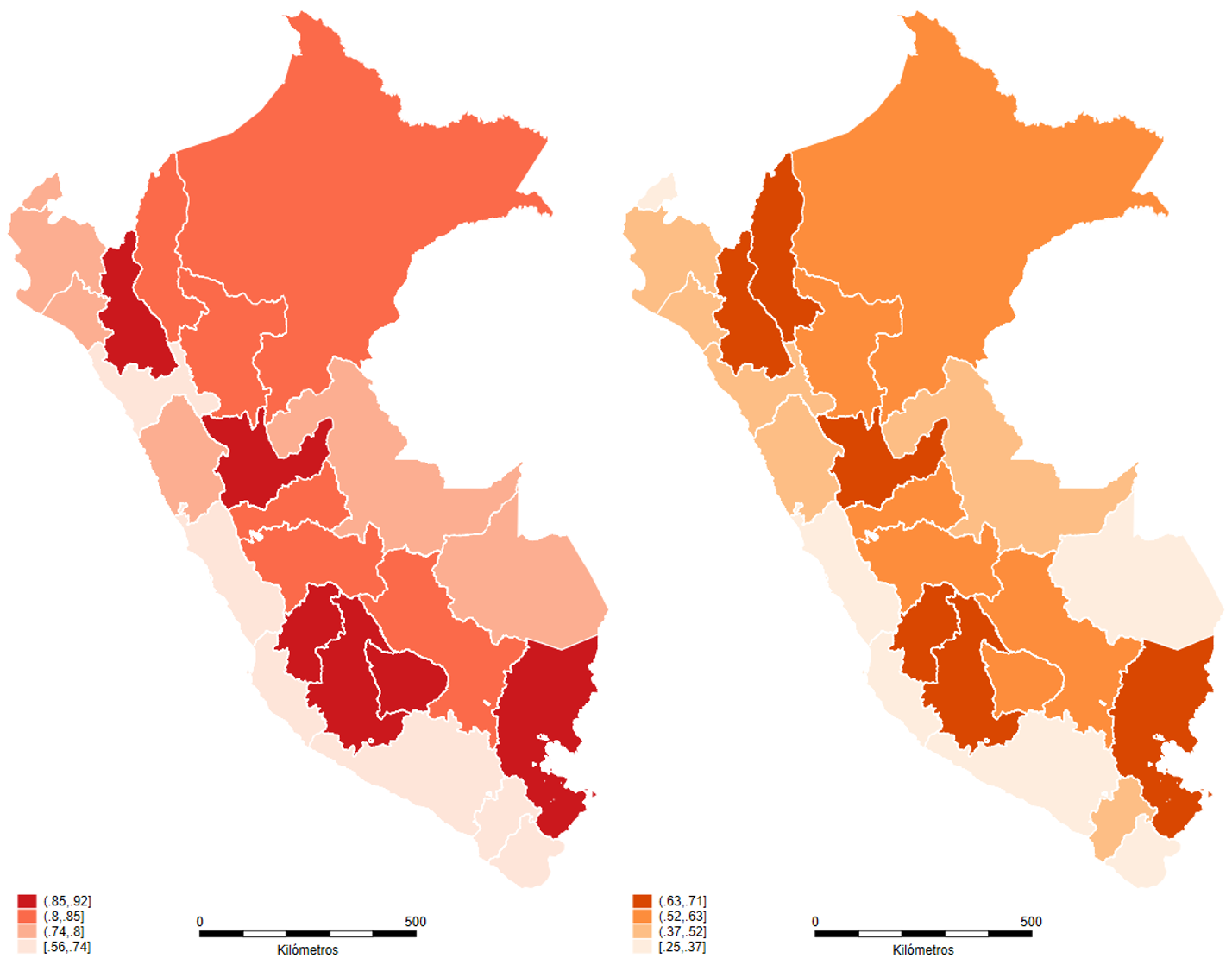

Spatially, workers with informal jobs are located mainly in rural areas and have a higher incidence in the Andes and jungle regions. Regarding the geographical scope, a higher informal employment rate is observed in rural areas (95.6%) compared to urban areas (65.7%). The geographic domains with the highest informal employment rates are Sierra Norte (87.9%), Sierra Centro (85.4%) and Selva (84.8%).

Although informality is seen as an indicator of job quality from the demand side (low qualification and absence of labor benefits), it is also closely related to an indicator from the labor supply side: underemployment (labor income and insufficient hours worked) which can be understood as an indicator of worker job satisfaction. In particular, 83.4% of the underemployed by income (invisible underemployment) and 95.8% of the underemployed by insufficient hours (visible underemployment) are informal workers.

Figure 3. Peru: Informality and underemployment by region, 2018 (percentages)

Source: ENAHO - INEI. Own elaboration.

Informal workers are mostly concentrated in less productive and labor-intensive economic sectors, they are mainly workers who work within households and work in small companies. In particular, the Agriculture, Home and Forestry sectors (85.6%); Transportation (85.6%) and Commerce; and, Construction (74%) employ more informal workers. By occupational category, the highest informality is found in unpaid family workers (100%, by definition), domestic workers (91.9%) and independent workers (89.3%). Regarding the size of the companies, it is observed that the highest levels of informality are found in the smallest companies: up to 20 workers (87.8%) and 21 to 50 workers (44.6%).

As in the case of the poor, informal workers have several characteristics that make them more vulnerable to the lack of economic activities since, by definition, they do not have any labor benefits nor will their employers continue to pay them a salary. Loayza (2008) points out that informality in employment in Peru does not have a single cause, but is a product of the combination of poor public services and a regulatory framework that does not allow formalization.

Throughout these two articles I have tried to provide more information on who will be most affected in the short term by the crisis caused by Covid19, but I have noticed that we were already in a deep crisis before the virus arrived: that of structural exclusion. Although it is important to attend to the present and its urgent needs, it is important not to lose sight of the problems that we have been dragging for many years. If today as a country it is so difficult for us to keep the population in their homes due to the risk of contagion, we should also try to understand that those who do so are often forced by great need. Today it is known that the government aid has not yet reached all those who need it most because there is a great problem of targeting and locating these people and also of the common leaks. Unfortunately, the existence of a small state has been added, with poor public services for poor people. We have much to do.

References

CEPLAN (2016). Economía informal en Perú: Situación actual y perspectivas. Lima: Centro Nacional de Planeamiento Estratégico.

Figueroa, A. (2015). Growth, employment, inequality, and the environment: Unity of knowledge in economics. Springer.

INEI. (2018). Producción y Empleo Informal en el Perú, Cuenta Satélite de la Economía Informal 2007-2017. Lima: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática.

Loayza, N. (2008). Causas y consecuencias de la informalidad en el Perú. Revista Estudios Económicos, 15(3), 43-64.

Schneider, F., & Enste, D. H. (2000). Shadow economies: size, causes, and consequences. Journal of economic literature, 38(1), 77-114.

In accordance with the Emergency Decree No. 033-2020 that the Independent Bond provides, other characteristics that potential beneficiaries must have: i) they must not be poor according to the General Register of Homes (PGH); ii) they must be in the geographical areas with the greatest health vulnerability; iii) they must not be recipients of other types of subsidies; and, iv) they should not have contracts with the public sector. ↩